Indice del volumen

Volume index

Comité Editorial

Editorial Board

Comité Científico

Scientific Committee

PERSISTENT AND ANEMIZING GROSS HEMATURIA SOLVED WITH ENALAPRIL.

Musso C, Mombelli C, Lizarraga A, Imperiali N, Algranati L

Servicio de Nefrología. Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires-Argentina

Rev Electron Biomed / Electron J Biomed 2005;3:29-34

Comment of the reviewer Javier Lavilla MD PhD. Departament of Nephrology. Clínica Universitaria. Universidad de Navarra. Pamplona. España

Comment of the reviewer Marta Patricia Casanova González MD. Departament of Nephrology. Hospital Universitario Clínico Quirúrgico "Dr. Gustavo Aldereguía Lima", Cienfuegos. Cuba

ABSTRACT

Hematuria is the presence of an excessive number of red blood cells in the urine (at least three or more erythrocytes in a high-power field in centrifuged urine). It is categorized as microscopic when it is visible only with the aid of a microscope and macroscopic when the urine is tea-colored, pink or even red.

Hematuria can result from injury to the kidney or injury to another site in the urinary tract, and renal hematuria can be caused by glomerular or non-glomerular disease.

Some clinical and biochemical findings contribute to understand the origin of this problem: the presence of hematuria with clots suggests an urological cause, while the presence of red blood cell casts and/or dysmorphic red blood cells in a urine sample supports a glomerular etiology.

In the present report we presented a clinical case of a patient suffering from persistent and anemizing gross hematuria secondary to a mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis associated with thick glomerular basement membranes which was solved using enalapril.

Key Word: mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis, macroscopic hematuria, enalapril

RESUMEN

La hematuria es definida como la presencia de por lo menos tres o más eritrocitos por campo en una muestra de orina centrifugada, pudiéndose a su vez clasificar este problema en microhematuria: cuando sólo puede ser detectado con la ayuda del microscopio o macrohematuria cuando a simple vista se observa una orina color te, rosada o francamente roja.

La hematuria puede ser producto de una lesión a nivel de la vía urinaria o a nivel renal, pudiendo ser esta última de etiología glomerular o no glomerular.

Algunos datos clínicos y bioquímicos contribuyen a la comprensión acerca del origen de la hematuria: la presencia de coágulos en la orina sugiere una causa urológica, mientras que la presencia de cilindros eritrocitarios y/o eritrocitos dismórficos o acantocitos en la misma apoyan una etiología glomerular.

En este reporte, presentamos un caso clínico de un paciente portador de una macrohematuria anemizante secundaria a una glomerulonefritis proliferativa mesangial asociada a la presencia de membranas basales glomerulares engrosadas, la cual se resolvió con el uso de enalapril.

Palabras clave: macrohematuria, glomerulonefritis mesangial, enalapril

INTRODUCTION

Hematuria is the presence of an excessive number of red blood cells in the urine: at least three or more erythrocytes in a high-power field in centrifuged urine 1. It is categorized as microscopic when it is visible only with the aid of a microscope and macroscopic when the urine is tea-colored, pink or even red. Only 5 ml of blood are needed to give pink macroscopic hematuria, while twice this blood volume will give easily visible hematuria2.

Even though the significance and seriousness of the finding of microscopic hematuria is independent of the number of the red blood cells, there is an increase in significant and life-threatening findings in relation to the quantity of blood in the urine if macroscopic hematuria is included in the analysis 2.

The first step in hematuria interpretation is to determine if it is of glomerular or non-glomerular origin. The former cause is mainly supported by the appearance in the urine of red blood cell casts, dysmorphic red blood cells (at least 30%), and /or a special type of them called acanthocytes: red cells with knob-like protrusions, in at least more than 1% 3.

In this report we presented a curious case of a persistent anemizing macroscopic hematuria of glomerular etiology which was solved using enalapril.

CASE REPORT

A twenty two year-old, male patient was referred to our Nephrology Department due to a two months of continuous gross hematuria. It had begun one year before suddenly with an episode of macroscopic hematuria that lasted three days. It disappeared spontaneously the first two times and the third time that it reappeared was two months before referral. That time the gross hematuria remained. This gross hematuria was never related to the presence of fever, sore throat nor to any infectious event. The patient had neither hypertension nor familiar antecedents of hematuria.

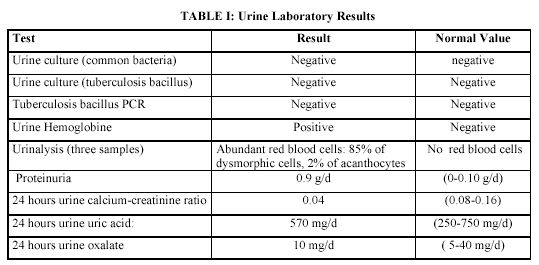

At the time of the nephrological consult we noticed that his urine had no clots and its red cells seemed to be of glomerular origin since it had a high proportion of dysmorphic red blood cells and acanthocytes (TABLE I).

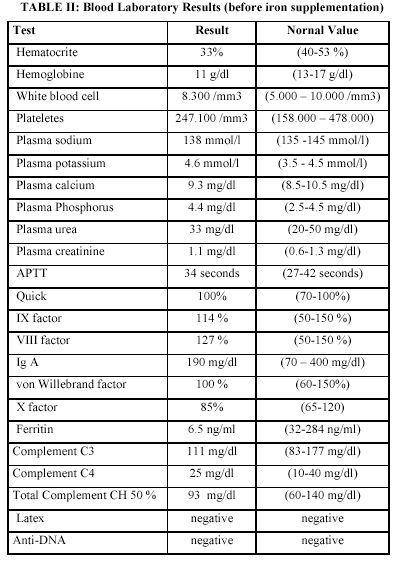

Renal imaging: ultrasound and TC scan were normal. The hematuria was so gross that it led him to low ferritin anemia which was solved prescribing iron supplements (TABLE II).

Despite the glomerular pattern of his hematuria, it was so gross that it appeared as a consequence of an active bleeding state. Because of that clotting studies and renal angiography, cystoscopy and intravenous pyelography were performed being all these studies normal.

Urinary infections included urinary tuberculosis were ruled out. He had neither crystalluria (calcium, oxalate nor uric acid), nor any antecedent of a renal trauma (TABLE I). Besides, he was neither on any drug that could generate papillary necrosis (non-steroidal anti-immflamatories, etc.), interstitial nephritis (diuretics, etc.) nor bleeding disorders.

Autoimmunity blood markers such as latex, anti-AND, etc were absent and creatinine clearance was compatible with the presence of glomerular hyperfiltration: 160 ml/min/1.73 m2.

A factitious hematuria was suspected but it did not explain the finding of dysmorphic blood red cells in his urine.

A renal biopsy was performed being the result as follows: optic microscopy was normal and immunological deposits were absent (an 8 glomeruli sample). Electronic microscopy showed irregular basament membranes, some of them thickened. However, there were no membrane lamination, lamina densa fragmentation or concomitant areas of glomerular membrane thinness. There was a mild increase of the mesangial matrix without deposits, tubules with occasional atrophy, interstitium with mild and focal fibrosis and normal vessels.

From this renal histology his hematuria was interpreted as secondary to a mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis. Regarding the documented increased in the basament membrane thickness, it was not interpreted as secondary to Alport syndrome since its typical histologic pattern was absent: membrane lamination, lamina densa fragmentation and concomitant areas of glomerular basement membrane thinness.

Moreover, hematologic, neurologic, oftalmologic and otorhinolaryngologic evaluation looking for alterations compatible with Alport syndrome were all normal.

A pharmacological treatment based on 5 mg/day of enalapril was iniciated in order to stop his hematuria and proteinuria. The therapeutical hypothesis was to obtain this objective through the reduction in the patient´s intra-glomerular pressure, which was suspected to be increased since his creatinine clearance was high.

A month later the hematuria has disappeared. This result persisted until the time of the present report (one year later).

DISCUSSION

The evaluation of a patient suffering from hematuria must consider the patient´s age and the clinical and biochemical characteristics of the hematuria. The former because an old age can evoke a neoplastic etiology, and the latter because the presence of a urine with clots and isomorfic red blood cells suggests a non-glomerular disease

3.

This initial approach enable the physician to organize the sequence of the following diagnostic tests. For instance, if a glomerular origin of the hematuria is suspected the logic procedure would be a renal biopsy, whereas if an urological cause is suspected the adequate study would be an urological endoscopy 2.

In the present clinical case the patient suffered from a persistent macroscopic hematuria without clots, with proteinuria and dismorfic urinary red blood cells. Even though most of the features of his hematuria were compatible with a glomerular origin, because of its persistence and the fact that it had led him to anemia (both features strongly related to non-glomerular etiology), we started his evaluation performing coagulation studies, renal angiography, cystoscopy and intravenous pyelography in order to rule out a bleeding disorder, a renal vascular malformation or an urological lesion respectively.

Studies for diagnosing paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria such as Ham test and sucrose test were also performed being all of them normal.

Since all these studies were normal and there were findings supporting a glomerular origin of the hematuria (ie: urinary dysmorphic red blood cells) afterwards, we decided to perform a renal biopsy. Its result was compatible with a mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis with concomitant presence of thick glomerular basement membranes4. The patient´s disease could not be defined as an Alport syndrome since there was a lack of all the other histological characteristics that this entity has 5,6.

Despite of the aforementioned concepts, a borderline sort of Alport syndrome can not be ruled out.

Even though, macroscopic hematuria could be the cause of the patient´s proteinuria, this could also be of glomerular origin since it had a glomerular pattern in the urine analysis, and the patient presented high creatinine clearance (hyperfiltration). Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors such as enalapril are used for treating hyperfiltration. Besides, in the thin glomerular basement membrane disease, it has already been proposed to use angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor as a means to reduce its associated hematuria. This strategy would be based on the reduction of the intra-glomerular pressure with the objective of minimizing the red blood cells passage through the altered glomerular barrier6.

Then, we decided to treat this patient with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor(5 mg/d) adding a potential benefit from it which was the impact of achieving a reduction in the intra-glomerular pressure in a patient who had his glomerular basement membranes altered (thickened): an analogical idea which came from the current proposed treatment for the thin glomerular membrane disease6.

As it had been thought with the treatment based on an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor: 5 mg/day of enalapril, the patient´s hematuria (even the microscopic one) and proteinuria disappeared completely and it has not return until the present report (one year later).

CONCLUSION:

Enalapril could be a therapeutic option for macroscopic hematuria due to mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis associated with thick glomerular basement membranes.

REFERENCES:

-

1.- Kokko J. Renal Diseases. In Bennett JC, Plum F (Eds). Cecil Textbook of Medicine. Philadelphia. W.B. Saunders. 1996: 513

2.- The patient with haematuria. In Cameron S (Ed). Oxford Textbook of Nephrology. Oxford. Oxford University Press. 2005: CD

3.- Falk R, Jennette C, Nachman P. Primary glomerular disease. In Brenner B (Eds) The KidneyPhiladelphia. Saunders.2005: 1294-1296

4.- Kashtan C. Alport Syndrome: an inherited disorder of renal, ocular, and cochelear basement membranes. Medicine. 1999: 338-355

5.- Glassock R. Hematuria and pigmenturia. In Massry S, Glassock R. (Eds). Textbook of nephrology. Baltimore. Williams & Wilkins.1989: 491-505

6.- Kashtan C, Sibley R, Michael A, Vernier R. Hereditary nephritis: Alport syndrome and thin glomerular basement membrane disease. In Tisher C, Brenner B (Eds). Renal Pathology. Philadelphia. JB Lippincott Company.1994: 1239-1265

7.- Knebelmann B, Grünfeld JP. Alport´s syndrome. In Cameron S (Ed). Oxford Textbook of Nephrology. Oxford. Oxford University Press. 2005: CD