Indice del volumen Volume index

Comité Editorial Editorial Board

Comité Científico Scientific Committee

PROVISION OF HEALTH CARE SERVICES IN CANADA: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

Rosa Rodriguez-Monguio, Ph.D.1,2, Enrique Seoane-Vazquez, Ph.D. 3,4, Fernando Antoñanzas Villar, Ph.D.5

1 School of Public Health and Health Sciences, 2 The Institute for Global Health, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

3 College of Pharmacy, 4 College of Public Health, The Ohio State University

5 Department of Economy and Business, University of La Rioja

rmonguio @ schoolph.umass.edu

Rev Electron Biomed / Electron J Biomed 2009;2:66-75

Comment of the reviewer Prof. Jaime Espin Balbino LLB, MBA, MSc. Andalusian School of Public Health (Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública). España

Comment of the reviewer Daniel A. Sepulveda Adams. Research Scientist, PRIME Institute. College of Pharmacy, University of Minnesota. Minneapolis, USA

RESUMEN:

El sistema sanitario de salud canadiense provee completo acceso a servicios hospitalarios y de atención ambulatorio, incluyendo servicios terapéuticos diagnósticos y preventivos. El nivel de cobertura de los servicios varía en el país. Este estudio examina las características principales de los sistemas canadiense de salud y de cuidados de larga duración; presenta un análisis estructurado del aseguramiento, financiación y provisión de los servicios sanitarios y de cuidados de larga duración; describe los principales desafíos de dichos sistemas; y concluye con una lista de oportunidades para la política sanitaria pública.

Los principales desafíos del sistema Canadiense están relacionados con el envejecimiento de la población, la prevalencia de enfermedades prevenibles causadas por hábitos no saludables, la cobertura y financiación de los cuidados de larga duración, la financiación de nuevas tecnologías y medicamentos de alto coste, y la escasez y inadecuada distribución geográfica de los profesionales sanitarios. Las oportunidades para la política sanitaria canadiense incluyen: fortalecer la política de salud pública, continuar con la transferencia de la atención al nivel ambulatorio, mejorar la coordinación entre los servicios de atención primaria y especializada, implantar un sistema nacional de planificación de recursos humanos, e integrar la atención domiciliaria como parte de la atención primaria de salud.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Canadá, política pública, salud pública, servicios sanitarios, cuidados de larga duración.

SUMMARY

The Canadian health care system provides comprehensive coverage of hospital and outpatient care, including therapeutic, diagnostic and preventive services. The level of coverage of services varies across the country. This study examines the key characteristics of the Canadian health and long-term care systems; presents a structured analysis of the insurance, financing and provision of health and long-term care services in Canada; describes the main challenges of the Canadian health and long-term care systems; and concludes with feasible opportunities for the Canadian health policy.

Main challenges to the Canadian system are related to population ageing; prevalence of avoidable diseases caused by poor health habits; coverage and financing of long-term care services; financing of expensive new technologies and pharmaceuticals; and the shortage and unbalanced geographic distribution of health care professionals. Opportunities for the Canadian health policy are: strengthening public health policy, continuing shifting care to the ambulatory level; improving the coordination between primary care and specialist services; implementing a system-wide national human resources planning; and integrating home-based care as part of overall primary health care.

KEY WORDS: Canada, public policy, public health, health care, long-term care.

1. INTRODUCTION

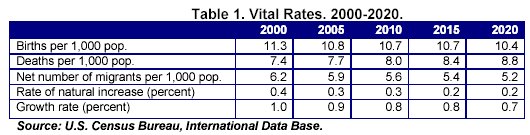

Canada had 31.6 million inhabitants in 20061, a population which is expected to reach 37.0 million by 20202. The crude birth rate was 11.3 per 1,000 population in 2000, and it is expected to decrease to 10.4 by 2020 (Table 1). The total fertility rate among women aged 15 to 49 declined to 1.53 in 20043; this rate is below the replacement level fertility for the total population without immigration (i.e. 2.11 per 1,000 women). The combined effects of the reduction of births, the net number of migrants and the increase in deaths are projected to reduce the population growth rate from 1.0% in 2000 to 0.7% in 20202. In 2006, Aboriginal people (i.e. First Nations, Métis and Inuit) accounted for 4% of the total population of Canada4. Canada's population as a whole is growing older. The proportion of people aged 65 years and over was 13.7% in 20061, and it is projected to increase to 18.2% in 20202.

The percentage of the Canadian population reporting good health status decreased from 89.2% to 88.2% for both genders and most age groups during the period 1994-20043. Circulatory diseases, including heart disease, were the leading causes of death, representing 31.4% of all deaths in 2002. Obesity and obesity-related morbidities are major public health problems. In 2005, 22.4% of the population aged 18 years and over was obese and 35.1% was overweight.

In 2003, First Nations reported difficulties in accessing health care including long waiting lists (33.2%); access to health services not covered under the Non-Insured Health Benefits Program (NIHB) (20.0%); availability of a health professional in rural and remote areas (18.5%); inadequate provision of health care (16.9%); and denial of prior approval for services under NIHB (16.1%)5.

The Canadian federal government's responsibilities include setting and administering national principles for the health system, providing financial support to the provinces and territories, and delivering primary and supplementary services to certain groups, including persons of Aboriginal ancestry, veterans of the Armed Forces and members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The federal government is also responsible for public health protection and regulation, consumer safety, and disease surveillance and prevention. It also provides support for health promotion and health research. Constitutionally health care is a matter of provincial jurisdiction. The provincial and territorial governments have most of the responsibility for organizing and delivering health care and other social services6: their role includes administering their health insurance plans, planning, paying for and evaluating hospital and outpatient care, and negotiating fee schedules for health professionals7.

This study examines the key characteristics of the Canadian health and long-term care systems and analyzes major challenges associated with the provision of health care, including the ageing population, prevalence of chronic diseases, and coverage of long-term care services. The paper provides a structured analysis of the regulation, insurance, financing and provision of health and long-term care services in Canada and assesses the major strengths and weakness of the country's provision of health and long-term care services. Finally, the paper describes the main challenges confronted by the Canadian health care system to overcome its current gaps, and presents health policy opportunities.

2. HEALTH CARE INSURANCE AND FINANCING

Under the Canada Health Care Act (1984), all residents of a province or territory are eligible to receive free medically necessary health services8. The Canada Health Act does not define the specific health services eligible for public coverage but sets general principles for the health care system. According to these principles, health care in Canada should be comprehensive in coverage; accessible without financial barriers; portable within the country and during travel abroad; and publicly administered.

Canada's health care system is organized in ten provincial and three territorial health insurance plans. Each provincial and territorial plan covers medically necessary hospital and outpatient medical care free of charge. Provinces and territories also provide coverage to certain population groups for health services that are not generally covered under the publicly funded health care system.

Private insurance for services insured under the Health Care Act is prohibited by provincial legislation in six provinces and discouraged in the other four through prohibitions of the subsidizing of private practice by public plans. Private insurance may covers the cost of supplementary services such as drugs, dental care, vision care, and complementary and alternative medicines and therapies6, 9. In 2003, 53.6% of dental care, 33.8% of prescription drugs and 21.7% of vision care was funded through private health insurance8. Most of the private health insurance is employment-based and is part of compensation packages, rather than privately purchased by individuals. Private health insurance for long-term care and home care is limited.

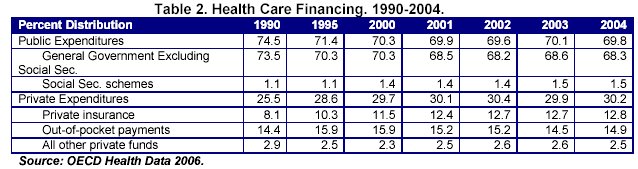

Canada has a predominantly public health care system financed through federal, provincial and territorial taxation. In 2004, 69.8% of total health care revenue came from public sources (mainly taxation) (Table 2). The federal government provides cash and tax transfers to the provinces and territories to finance health care services through the Canada Health Transfer6.

All provinces manage single-payer systems for the delivery of hospital, physician and diagnostic services; provinces fund hospitals through health districts. Hospitals are paid through annual global budgets negotiated with the provincial and territorial ministries of health, or with a regional health authority10. The vast majority of specialists and general practitioners work under fee-for-service schedules; fees for health care providers are negotiated directly with the provincial ministry in a contractual relationship with regional health authorities (RHAs). General practitioners operate largely outside the RHA system8. Most health care personnel, including nurses (i.e. registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, psychiatric nurses and nurse practitioners), are salaried.

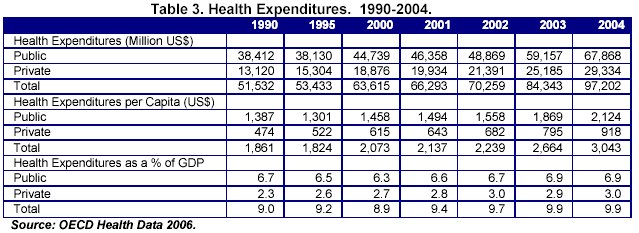

Canada spent US$97,202 million on health in 2004 (Table 3). Health expenditures represented 9.9% of its GDP in 2004, which was above the OECD average for health expenditures3. Expenditures per capita were US$3,043 in the same year11.

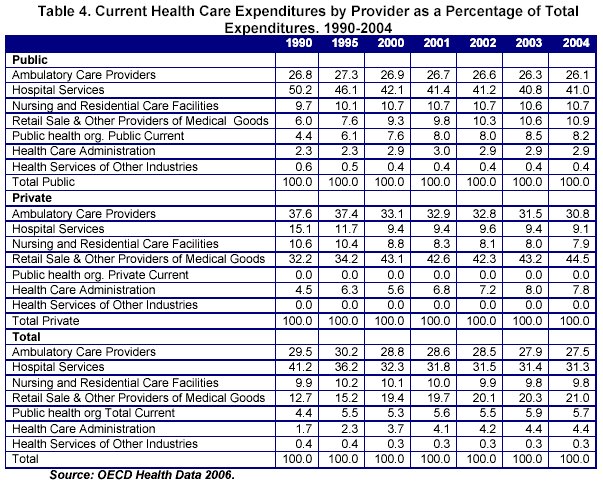

Also in 2004, hospital services, excluding capital expenditures, accounted for 31.3% of health expenditures (Table 4), ambulatory care providers for 27.5%, pharmaceutical expenditures for 16.9%, and nursing and residential care facilities for 9.8%3. Health expenditures are projected to reach $147.0 billion (inflation-adjusted) in 2020. Health expenditures vary across the provinces and territories due to differences in the services that each province and territory covers, and in demographic factors such as the population's age.

3. PROVISION OF HEALTH AND LONG-TERM CARE

Provinces in Canada work through, or contract with, a large range of health care organizations and providers, from RHAs to individual hospitals and physicians. RHAs act as both purchasers and providers: the majority of acute care facilities, including their salaried employees, are managed directly by RHAs, and some RHAs contract with private providers for the provision of specialized ambulatory care services. Nursing homes and other long-term care facilities are either run directly by RHAs or have a contractual relationship with them. Family physicians provide the majority of primary medical care services in Canada. Most physicians work in their own private clinics. Patients have freedom of choice in selecting a family physician, and such general practitioners act as gatekeepers to access to specialist and hospital services.

Recent reforms in Canada have focused on increasing the number of community primary care centers that provide services around the clock; placing greater emphasis on promoting health, preventing illness and injury, and managing chronic diseases; increasing coordination and integration of comprehensive health services; and improving the work environment of primary care providers6. There is also an increasing interest in expanding the roles of nurses and pharmacists in primary care. Many provinces are changing their laws to enable nurse practitioners to deliver a broader range of primary care services. Moreover, some jurisdictions are setting targets concerning the replacement of fee-for-service remuneration by alternative payment mechanisms, encouraging physicians' engagement in the provision of essential services around the clock, and accelerating the development of medical telephone call centers.

Publicly owned hospitals perform the majority of the secondary, tertiary and emergency care, as well as the majority of specialized ambulatory care and elective care. Although hospitals provide mainly acute care, some comprehensive hospitals also provide extended or chronic care, rehabilitation and convalescent care, and psychiatric services; hospitals also manage nursing stations and outpost hospitals in remote areas. Canadian hospitals are organized and administered on a local basis, with almost all hospitals operating at arm's length from provincial and territorial governments.

Canada has experienced a decline in the number of hospitals. The total number of hospital beds was relatively stable until the mid-1980s, but began to decline after 1985-1986. Hospital beds fell rapidly in the 1990s. Trends appear to be stabilizing at present12. There were 746 hospitals with 115,120 beds in 2002-200313. Approximately 8 in 100 Canadians were hospitalized in 2005-2006, representing a decrease of 24.6% since 1995-1996. The decline in hospital beds and the rate of hospitalization are due to a number of factors, including clinical practice changes and new surgical techniques14. The number of days spent in acute care hospitals was 20.3 million in 2005-2006, representing a 13.1% decrease since 1995-199615.

A considerable amount of hospital care has been shifted from inpatient settings to ambulatory clinics12. In 2003, 35.9% surgical procedures were done in the hospital and 64.1% in ambulatory settings3. An increasing number of surgeries are being performed in a day surgery setting (up by 30.6%) compared to an inpatient hospital setting (down by 16.5%) over the past decade15.

Between 1990 and 2004, the number of general practitioners for every 1,000 people decreased from 1.1 to 1.0, and the number of practicing specialists increased from 1.0 to 1.13. In 2006, the number of physicians for every 100,000 population was 190 (98 family medicine physicians, 92 specialists). In 2006, the ratio of physicians per 100,000 population among the provinces ranged from 36 in Nunavut to 226 in Yukon Territory16.

Nurses are the largest group of health care workers in Canada, though in the last 20 years, the supply of nurses has fluctuated significantly17. Between 1990 and 2004, the number of practicing nurses for every 1,000 people decreased from 11.1 to 9.93. In 2005 the ratio of registered nurses employed in nursing among the provinces and territories ranged from 1:76 in Northwest Territories to 1:153 in British Columbia18, 19. The average age of registered nurses in 2006 was 45.0 years, 4.4 years older than that of the rest of the country's workforce20, 21.

Canada Health Act does not cover long-term care services. Nevertheless, all provinces and territories provide and pay for certain long-term care services. In 2001, provincial programs and subsidies for long-term care, home care, community care, and public health and prescription drugs dispensed in long-term care facilities amounted 23% of total health expenditures. Home care expenditures increased from $26 million in 1975 to approximately $2.7 billion in 2001, and nursing home expenditures also increased from $800 million to $6.8 billion over the same period17. Referrals to long-term care institutions can be made by doctors, hospitals, community agencies, families, and the patient him/herself; needs are assessed and services are coordinated to provide comprehensiveness and continuity of care.

There is large variability across Canada in the type of services offered in long-term care facilities. In general, long-term care facilities provide living accommodation for people who require on-site delivery of continuous supervised care, including professional health services, personal care and services such as meals, laundry and housekeeping. Provincial and territorial governments finance health care services provided in long-term care institutions, and individuals pay out-of-pocket for room and board; in some cases, the provincial and territorial governments subsidize these out-of-pocket payments.

Some nursing homes are managed directly by the RHAs, but a large number remain independent companies, often in a contractual relationship with the RHA to provide a defined level of long-term care. There is also a for-profit nursing home sector providing various levels of care, mostly to the elderly.

Demand for home care has increased due to an ageing population and other societal developments. The availability of family members for informal care is expected to continue to decline due to reductions in family size and increasing mobility. Home care services generally include nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy and personal care including assistance with the activities of daily living. Some provinces and territories provide complete coverage for certain services while others provide more limited home care services according to acuity of illness, financial means, dollar limits, or other criteria. With the exception of British Columbia, where eligibility requires 12 months of residency, general eligibility requirements for home care across Canada require three months' residency; a health insurance card; a health or medical need for care; a suitable home for care; and a physician referral.

Since the 1970s, home care services have been funded through a combination of provincial and territorial funds, federal funds, private insurance, and out-of-pocket payments. The federal government provides funding support through transfer payments for health and social services, and some provinces use means testing to determine access to home care services; on average, provinces and territories spend between 4% and 5% of their health budgets on home care. Between 1980 and 2000, the average annual rate of growth for these expenditures was 14%, compared with 7.1% for all provincial-territorial health expenditures17.

Informal caregivers play an essential role in the delivery of home care services in Canada and also provide ongoing care, support and advocacy for people with physical disabilities17, 22. Overall 18% of the Canadian population 15 years of age or older provide unpaid care or assistance to seniors23 and 85% to 90% of home care is provided by family and friends 24, 25. Each province and territory has its own policies and programs concerning support and services for informal caregivers. Respite services for informal caregivers are provided through a home care worker coming to the home, a patient being placed in a respite bed in a long-term care facility for a short-term stay or a mixture of services22, 26; the availability of such services across Canada varies widely depending on provincial/territorial financial resources and the availability of qualified workers. Additionally, the Compassionate Family Care Benefit was introduced in 2004 to support those who need to leave their job temporarily to care for a gravely ill or dying child, parent or spouse. Policies also vary across Canada with respect to allowances for the cared-for person and the caregiver.

4. CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE CANADIAN HEALTH POLICY

Canada's health care system faces major challenges related to demographic changes; prevalence of avoidable diseases caused by poor health habits; coverage of health care services, especially long-term care services; and the shortage and unbalanced geographic distribution of health care professionals. Demographic patterns in Canada over the long-term are characterized by demographic ageing, the slowing of the increase of the natural rate of population and cultural diversity resulting from high rates of immigration. Aboriginal health is also a matter of concern of federal jurisdiction27, 28. The demographic and epidemiological trends represent a growing threat for the Canadian welfare state. Prevalence of avoidable diseases caused by poor health habits is a threat to the health of Canadians. Obesity is becoming more prevalent among Canadians, and it is increasing among children.

Health coverage levels vary across the country, from full financial protection for all necessary healthcare services to some exclusions and cost-sharing arrangements. Timely access to health care also remains as a concern associated with the provision of care to rural and remote populations, and with the cultural diversity resulting from high rates of immigration29.

Challenges to the Canadian system are also related to the coverage and financing of long-term care services. Canada has established long-term care programs under the auspices of health and welfare services: across the country, provincial and territorial governments offer a different range of services covered under a variety of cost-sharing arrangements and eligibility requirements. However, lack of minimum standards and coverage criteria across the country could erode the equity of the welfare system.

The demand for long-term care services will continue to increase due to a combination of economic and socio-demographic factors, including improvements in treatment outcomes, bed closures, and reductions in length of stay, improvements in homecare services, and the ageing of the population. Demographic ageing, the increased participation of women in the labor market, higher levels of geographical mobility, a lower ratio of working age people to elderly, and changes in family structure may also affect the extent to which long-term care is provided.

Changes in how health care services are organized and delivered in hospitals and other settings have had a direct effect on the workload of health professionals, particularly nurses, and their competencies. Professional dissatisfaction and unbalanced distribution of health care professionals have led to increased problems of health care delivery in Canada30.

Canada also faces a number of challenges in terms of supply, distribution, retention, recruitment, and training of health care professionals16, 19, 31. Based on existing trends, the proportion of family physicians is expected to decrease over time and forecasting studies predict shortages in family physicians in Canada; some specialties will experience shortages as well (e.g. geriatricians)32. There are also nursing shortages in certain practice areas and an uneven distribution of nurses across geographic regions, especially in rural and remote areas. The problem of attracting health care providers to rural communities is exacerbated by competition among provinces and territories. The current shortage of nurses could also worsen: at a time when an ageing population will require more nursing services, a large cohort of nurses will be retiring and will not be replaced by a similar number of new graduates21.

Long-term care is a labor-intensive sector and the sector is also likely to suffer from acute labor shortages related to ageing of health professionals. Additionally, as home care services continue to expand, there will be growing demands for trained home care workers, and population ageing and labor shortage could drive up the cost of providing long-term care services. To some extent, shortages may also explain the lack of capacity in institutional long-term care, which results in elderly people occupying hospitals' acute care beds for longer than necessary, as well as a decline in the quality of services provided.

Alongside its challenges, the Canadian health care system has valuable opportunities that can be grouped under three main areas: epidemiological trends, delivery of health care and human resources. The country could strengthen public health measures to tackle poor health habits of the population: in 2002, the federal, provincial and territorial health ministers launched the Integrated Pan-Canadian Healthy Living Strategy, an intergovernmental plan which attempts to improve the state of knowledge and coordinate governmental and voluntary initiatives, all encouraging physical activity, healthier eating and tobacco cessation8, 33.

Canadian public health activity focuses on the traditional roles of health protection and behavioral approaches to health promotion33, 34. A broader approach to public health policy has been proposed based on the following strategies35, 36: reducing the prevalence of risk factors (tobacco, nutrition, physical activity, alcohol consumption, overweight and obesity, hypertension, high cholesterol) associated with disease; reducing the burden of chronic disease; advancing comprehensive population-based interventions; reducing inequities in risk factors and in access to services due to cultural, social, economic and geographic disparities, especially for Aboriginal populations; engaging researchers, policy-makers and practitioners for policy and program development proposes; raising public awareness of the broader determinants of health; aligning national public health policies with those of the provinces and territories.

As of result of task transfers from secondary care, there is a trend towards expanding responsibilities in primary care, as well as a stronger involvement of primary care professionals in screening, prevention and health promotion services. Continuing shifting care to an ambulatory level and improving coordination between primary care and specialist services could improve the effectiveness of health-care delivery, reduce fragmentation of the delivery process and contain health expenditures without jeopardizing health outcomes.

Additionally, informal caregivers play a growing role in providing care in Canada. Informal care and self-care are substituting for services otherwise provided in institutional settings and by professionals. It is essential to provide appropriate institutional support to caregivers and to integrate effective home-based and other long-term care as part of the country's health and social systems. It is also important for the future sustainability of the Canadian health and long-term care systems to ensure that home-based care is an integral part of overall primary health care.

One major policy issue for workforce development is the extent to which countries allow nursing assistants to perform certain tasks currently performed by nurses (e.g., administering medications, providing wound care and changing catheters). Giving long-term care workers added responsibility and autonomy might motivate them to remain in the job, or to encourage others to seek these positions.

There is no a national agency responsible for system-wide national human resources planning in Canada - most planning is done within the ministries of health at the provincial level. The Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Canadian Institute for Health Information is a step forward towards implementation of a comprehensive information system to monitor the actual number of health care workers and to forecast the stock and distribution of health care professionals by practice settings37.

It is also recommended that the country identify and support the implementation of retention strategies for the health care workforce32. Key strategies could include addressing appropriate nurse/patient ratios; encouraging efficient team-based working relationships; reducing non-nursing duties; preventing workplace injuries and illness; implementing improved flexibility and family-friendly scheduling options; and increasing childcare support. It is also essential to increase training and employment opportunities for graduating students, and to provide appropriate support within the workplace to ensure their integration within the nursing profession38. Like other countries experiencing health care personnel shortages, Canada is also considering salary increases39, but policies focusing heavily on such increases have only limited success40, 41.

The Canadian International Medical Graduate (IMG) Taskforce made six recommendations which were endorsed by the federal/provincial/territorial Ministers of Health in 200442. These recommendations include: to increase the capacity to assess and prepare IMGs for licensure; to work towards standardization of licensure requirements; to expand programs to assist IMGs with the licensure process and requirements in Canada; to develop capacity to track and recruit IMGs; and to develop a national research agenda. Many countries rely on immigration of health professionals to address labor shortages, but while inward migration could partially mitigate the shortages of health care professionals in the short term, these are still narrow approaches, particularly in rural areas.

REFERENCES

1. U.S. Census Bureau. International Database, 2007. http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb/

2. Canada's National Statistical Agency. Statistics Canada, 2006 Census. Canada, 2008. http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/popdwell/Table.cfm?T=101.

3. OECD . Heath Data. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2006.

4. Minister of Industry. Statistics Canada. Aboriginal Peoples in Canada in 2006: Inuit, Métis and First Nations, 2006 Census. Census year 2006. Canada, 2008. http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/analysis/aboriginal/pdf/97-558-XIE2006001.pdf

5. Minister of Health (2006a), Healthy Canadians. A Federal Report on Comparable Health Indicators. Minister of Health. Canada, 2006.

6. Health Canada, Canada's Health Care System, 2005. Available online at: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca

7. Evans R, Roos NP. What is Right about the Canadian Health Care System?. The Milbank Quarterly. 1999; 77:393-399.

8. Marchildon GP. Health Systems in Transition: Canada. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Copenhagen, Denmark, 2005.

9. Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association. The Role of Supplementary Health Insurance in Canada's Health System. Submission to the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada. Toronto, Canada, 2001.

10. Sheils JF, Young GJ, Rubin RJ. O Canada: Do we Expect too much from its Health System?. Health Affairs. 1992; 11, 7-20.

11. European Observatory on Health Care Systems. Health Care Systems in Eight Countries: Trends and Challenges. Edited by Dixon A. and Mossialos E. Commissioned by the Health Trends Review, HM Treasury. London, UK. 2002.

12. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Hospital Trends in Canada. National Health Expenditure Database. March 25, 2005. Ottawa, Ontario, 2008. http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/dispPage.jsp?cw_page=AR_1215_toc_e.

13. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Canadian MIS Database. 2008.

14. Evans RG, McGrail KM, Morgan SG, Barer ML, Herzman C. Population Aging and the Future of Health Care Systems. Can J Aging. 2001;20:160-191.

15. Canada Institute for Health Information. Inpatient Hospitalizations and Average Length of Stay Trends in Canada, 2003-2004 and 2004-2005. Hospital Morbidity Database and the Discharge Abstract Database. Canada, 2005. http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/dispPage.jsp?cw_page=bl_hmdb_3jan2007_e. Accessed June, 2008

16. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Supply, Distribution and Migration of Canadian Physicians, 2006. Health Human Resources Database. Ottawa, Ontario, 2007. http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/splash.html

17. Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada. Building on Values the Future of Health Care in Canada. Roy J. Romanow Commissioner. Canada, 2002. http://www.cbc.ca/healthcare/final_report.pdf

18. Canadian Nurses Association. Workforce Profile of Registered Nurses in Canada. Canada, 2005. http://www.cna-aiic.ca/CNA/resources/bytype/statistics/default_e.aspx.

19. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Distribution and Internal Migration of Canada's Registered Nurse Workforce. Health Human Resources Database. Ottawa, Ontario, 2007. http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/splash.html.

20. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Statistics Canada and Health Canada. Findings from the 2005 National Survey of the Work and Health of Nurses. Statistics Canada, Ministry of Industry. Ottawa, Ontario, 2006.

21. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Workforce Trends of Registered Nurses in Canada. Health Human Resources Database. Ottawa, Ontario, 2006. http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/splash.html

22. Keefe JM, Manning M. The Cost Effectiveness of Respite: A Literature Review. Health Canada Home and Continuing Care Policy Unit Health Care Policy Directorate. Halifax, Nova Scotia, 2005. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/alt_formats/hpb-dgps/pdf/pubs/2005-keefe/2005-keefe-eng.pdf

23. Statistics Canada. Unpaid Work. Census Technical Report. Catalogue No. 97F0013XCB2001003 Topic-based Tabulations, Canada's Workforce: Unpaid Work. Statistics Canada 92-397-XIE, Ottawa, Ontario 2005. http://www.statcan.ca

24. Ontario Coalition of Senior Citizens' Organizations. Presentation to the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada, Sudbury Public Hearing. Sudbury, Ontario, 2006.

25. Family Caregivers Association of Nova Scotia. Presentation to the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada, Halifax Public Hearing. Halifax, Nova Scotia, 2002.

26. Dunbrack J. Respite for Family Caregivers an Environmental Scan of Publicly-funded Programs in Canada. Health Canada, 2003. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/alt_formats/hpb-dgps/pdf/pubs/2003-respite-releve/2003-respite-releve-eng.pdf

27. Frohlich KL, Ross N, Chantelle R. Health Disparities in Canada Today: Some Evidence and a Theoretical Framework. Health Policy. 2006; 79: 132-143

28. Statistics Canada. Projections of the Aboriginal Populations, Canada, Provinces and Territories. Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 91-547-XIE. Canada, 2005

29. Wilson K, Rosenberg MW. Accessibility and the Canadian health care system: squaring perceptions and realities. Health Policy. 2004;67: 137-148

30. Eike-Henner WK. The Canadian Health Care System: An Analytical Perspective. Health Care Analysis. 1999; 7: 377-391.

31. Sameer R, Kisalaya B. Interprovincial Migration of Physicians in Canada: Where are they Moving and Why? Health Policy. 2006;79: 265-273

32. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Canada's Health Care Providers, 2007.

33. Raphael D, Bryant T. The State's Role in Promoting Population Health: Public Health Concerns in Canada, USA, UK, and Sweden. Health Policy. 2006;78: 39-55

34. Dennis R. Barriers to Addressing the Societal Determinants of Health: Public Health Units and Poverty in Ontario, Canada. Health Prom Int. 2003;18: 397-405.

35.Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance of Canada. Primary Prevention of Chronic Diseases in Canada: A Framework for Action. Canada, 2008. http://www.cdpac.ca/media.php?mid=451

36. Low J, Thériault L. Health Promotion Policy in Canada: Lessons Forgotten, Lessons Still to Learn. Health Prom Int. 2008;23: 200-206

37. Bloor K, Maynard A. Planning Human Resources in Health Care: Towards an Economic Approach: An International Comparative Review. Canadian Health Services Research Foundation. Ottawa, Ontario, 2003. http://www.chsrf.ca

38. Advisory Committee on Health Delivery and Human Resources. The Nursing Strategy for Canada. Ottawa, Ontario, 2003. http//www.hc-sc.gc.ca/english/nursing

39. Scanlon WJ. Nursing Workforce: Recruitment and Retention of Nurses and Nurse Aides Is a Growing Concern. Testimony before the Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, U.S. Senate, GAO-01-750T, U.S. General Accounting Office, Washington DC, 2001. http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d01750t.pdf

40. Buchan J, Maynard A. The Health Care Workforce in Europe: Learning from Experience. In Bernd R, Carl-Ardy D, Martin M, editors. World Health Organization; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006.

41. Docteur E, Oxley H. Health-Care Systems: Lessons from the Reform Experience Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD. Paris, France, 2003.

42. Minister of Health. Pan-Canadian Health Human Resource Strategy 2005-2006 Annual Report. Canada, 2006.

Correspondence:

Rosa Rodriguez-Monguio, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

University of Massachusetts. Amherst -School of Public Health and Health Sciences. USA

E-mail: rmonguio @ schoolph.umass.edu