Indice del volumen Volume index

Comité Editorial Editorial Board

Comité Científico Scientific Committee

- Self-regulation of the renal flow (SRRF)

- Tubule - glomerular feed-back (TGFB)

PERFUSION PRESSURE AND RENAL BLOOD FLOW: THEIR RELATIONSHIP AND DIFFERENCES

Carlos G. Musso, MD. PhD.1,2, Manuel Vilas, MD.2,

Jose R. Jauregui, MD. PhD1

1Unidad de Biología del Envejecimiento, y 2Servicio de Nefrología y Medio Interno

Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires.

Buenos Aires. Argentina

Rev Electron Biomed / Electron J Biomed 2014;2:42-45.

Versión en español

Comment of the reviewer Dr. Ricardo M Heguilén. Médico Nefrólogo. Unidad de Nefrología. Hospital Juan A Fernández. Coordinador del Grupo de Trabajo de Fisiología Clínica Renal. Sociedad Argentina de Nefrología. Buenos Aires. Argentina

Comment of the reviewer Dra. Amelia Bernasconi. Medica Nefrológa. Especialista en Trasplante renal. Jefe de Departamento de Medicina del Hospital J.A.Fernandez. Buenos Aires. Argentina.

SUMMARY:

PERFUSION PRESSURE AND RENAL BLOOD FLOW: THEIR RELATIONSHIP AND DIFFERENCES

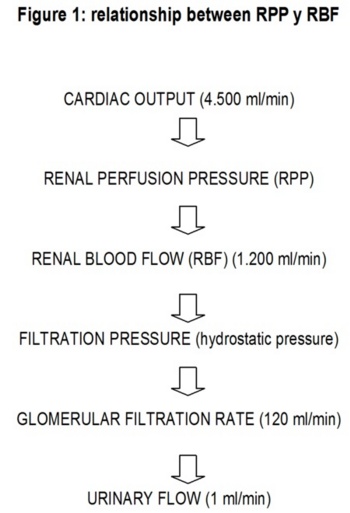

The concepts of renal perfusion pressure (RPP) and renal blood flow (RBF) are usually confused, but although they are intimately related, they are not strictly the same. RPP originates from the minute cardiac volume and is, therefore, the cause of RBF, which generates glomerular filtration and as a consequence, also induces the urinary flow.

On the other hand, whereas RPP can be subject to fluctuations, the same happens to RBF though at a much lower level due to the existence of physiological mechanisms, such as self-regulation of the flow and tubule-glomerular feed-back. We conclude that there is a dependence of the RBF in relation with RPP, with the former acting as the final responsible of the glomerular filtration.

KEYWORDS: perfusion pressure. Blood flow. Kidney.

RESUMEN:

A menudo se confunden los conceptos de presión de perfusión renal (PPR) y flujo sanguíneo renal (FSR), los cuales si bien están íntimamente relacionados, no son estrictamente iguales. Mientras que la PPR nace del volumen cardíaco minuto y es por ende promotora del FSR, éste último es generador del filtrado glomerular y en consecuencia del flujo urinario.

Por otra parte, mientras la PPR puede estar sujeta a fluctuaciones, el FSR lo está en mucha menor medida merced a la existencia de mecanismos fisiológicos, tales como la autoregulación de flujo y la retro-alimentación tubulo-glomerular.

Concluimos que existe una dependencia del FSR respecto de la PPR, siendo no obstante el FSR el responsable final del filtrado glomerular.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Presión de perfusión. Flujo sanguíneo. Riñón.

INTRODUCTION

The intention of this article is to describe, in a clear manner, the relationships and differences between renal blood flow (RBF) and renal perfusion pressure (RPP).

RBF whose normal value is around 1.200 ml/min in the young, and 600 ml/min in the healthy old, is the main cause of renal filtration pressure, which originates from the hydrostatic pressure of the glomerular capillary, which is the motor force of the glomerular filtration rate: 120 ml/min/1.73 m2 (young), 70 ml/min/1.73 m2 (old) and 50 ml/min/1.73 m2 (very old). Finally, it is this glomerular filtration that induces urinary flow, which depends on their hydration status, which is normally around 1 ml/min (Figure 1)1,2. Likewise, the cardiac output, whose normal value is around 4.500 ml/min, leads to RPP, which in turn, contributes to RBF (Figure 1).

Regarding RBF, the total amount of variables that determine it, they are specified in its formula, as follows1:

RBF = [renal blood pressure - renal venous pressure] ( P) / renal vascular resistance (R)

Therefore, FSR = (

P) / renal vascular resistance (R)

Therefore, FSR = ( P / R)

P / R)

Additionally, there are mechanisms that procure that the fluctuations in RPP do not translate in oscillations in RBF. These regulatory mechanisms are:

SRRF: The fact that the variations in blood pressure do not translate into big changes of glomerular filtration rate, so that the blood flow and the glomerular filtration are maintained almost constant within a relatively wide range of RPP (80 - 180 mmHg), is due precisely to the changes that occur in the pre-capillary resistance. This phenomenon is known as self-regulation of the renal flow. Thus, we note a decrease in the diameter of the afferent arteriole (via miogenic reflex) when the perfusion pressure increases, it prevents the transmission of this pressure increase to the glomeruli, thus avoiding a significant change in the hydrostatic pressure of the glomerular capillary, and therefore in the glomerular filtration rate. On the contrary, when the renal perfusion pressure drops, the glomerular filtration rate can be maintained at the expense of a dilation of the afferent arteriole3-5.

Regarding TGFB, it is the following phenomenon: when the filtration volume at a glomerular level reaches the final sector of the thick ascending loop of Henle, more specifically the area known as macula densa, its cells, fitted with an apical co-transporter NaK2Cl, detect the urinary fluctuations of chloride (sodium), so if a drop in the glomerular filtration rate reduces the arrival of chloride (sodium) to the macula densa, then an local response is initiated (mediated by the release of adenosine or nitric oxide) which leads to a dilation of the afferent arteriole and the subsequent increase in RBF, and consequently in the glomerular capillary hydrostatic pressure. On the contrary, the increase in the glomerular filtration rate determines the arrival at a higher concentration of chloride (sodium) to the macula densa, a suppression of the release of the above mentioned substances, with the subsequent constriction of the afferent arteriole, the drop in RBF and glomerular filtration rate. Therefore, not only does this TGFB keep the glomerular filtration rate at a constant level, but also the distal tubular flow4-6.

It is important to point out that an increase in RPP usually induces a higher increase in the diuretic rhythm than in the glomerular filtration rate. This is due to the fact that the increase in RPP not only elevates hydrostatic pressure in the glomerular capillary, but also in the peritubular capillary, which alters the Starling forces (increase in the hydrostatic pressure of the peritubular capillary) between those capillaries and the tubular lumen, which leads to a decrease in the tubular reabsorption of water, with the subsequent increment in urinary volume (pressure diuresis). It is for this reason that oliguric kidney failure secondary to hypotension, usually recovers its diuretic rhythm before its glomerular filtration rate, when arterial blood pressure improves. Therefore, in this context, the increase in urinary flow should not be equivalent to an improvement in the kidney function, since the latter could just be secondary to a phenomenon of "pressure diuresis"1,7.

Hence, we conclude that RBF depends on RPP, although the former is the final responsible for the glomerular filtration.

REFERENCES

1.- Licardi E, Calzavacca P, Bellomo R. Renal blood flow and perfusion pressure. In Ronco C, Bellomo R, Kellum J (Eds.). Critical Care Nephrology. Philadelphia. Saunders. 2009: 174 -178

2.- Rennke H, Denker B. Renal pathophysiology: The essentials. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2007

3.- Guyton AC, Hall JE. Manual de Fisiología Médica. Madrid. McGraw-Hill-Interamericana. 2002

4.- Ortiz Arduán A, Tejedor Jorge A, Rodríguez Puyol D. Fisiopatología del fracaso renal agudo. En Hernando Avendaño L (Ed.). Nefrología Clínica. Buenos Aires. Panamericana: 739-747

5.- Dworkin LD, Brenner BM. The renal circulations. In Brenner BM, Levine S (Eds). Philadelphia. Saunders. 2004: 309-352

6.- Maddox DA, Brenner BM. Glomerular Ultrafiltration. In Brenner BM, Levine S (Eds). Philadelphia. Saunders. 2004: 353-412

7.- Porth C. Fundamentos de Fisiopatología. Mexico. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2012: 499-508

CORRESPONDENCIA:

Carlos G. Musso, PhD

Servicio de Nefrología y Medio Interno

Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires (HIBA).

Buenos Aires.

Argentina

Mail: carlos.musso @ hospitalitaliano.org.ar

Comentario del revisor Dr. Ricardo M Heguilén.

Médico Nefrólogo. Unidad de Nefrología. Hospital Juan A Fernández. Coordinador del Grupo de Trabajo de Fisiología Clínica Renal. Sociedad Argentina de Nefrología. Buenos Aires. Argentina

Muchas veces nos preguntamos cuál es la razón por la cual en la literatura médica, incluso en revistas científicas con alto factor de impacto, abundan las publicaciones que abordan temas declarados controversiales pero que resultan finalmente por demás obvios. Resulta así ser que muchas veces lo obvio es materia de controversia y la controversia se genera más por una confusión de términos y conceptos que por lo debatible del hecho biológico o físico en sí mismo.

El presente artículo "Presión de perfusión y flujo sanguíneo renal, sus relaciones y diferencias" pareciera generado y concebido interpretando esa dualidad. Así es que si bien desde una visión meramente intuitiva pareciera fácil dilucidar la diferencia entre presión y flujo, ya que la primera implica el concepto físico de fuerza y flujo el de caudal (o sea cantidad de materia o fluido que circula por un área dada en la unidad de tiempo) estos conceptos, en su aplicación en fisiología y fisiopatología renal no resultan claros y como bien los autores pertinentemente resaltan, muchas veces se confunden.

El Dr. Carlos Musso y coautores logran transmitir estos conocimientos con extrema sencillez y claridad sin igual en este artículo profundo pero a la vez de muy amigable lectura.

Comentario de la revisora Dra. Amelia Bernasconi.

Medica Nefrológa. Especialista en Trasplante renal. Jefe de Departamento de Medicina del Hospital J.A.Fernandez. Buenos Aires. Argentina.

El articulo causa del presente comentario recoge la experiencia del Dr. Carlos Musso dedicado a la exploración de la función renal desde sus inicios en la Nefrología.

No se trata de un tema más a investigar, sino que por el contrario, circunscribe un concepto que resulta a menudo difícil de comprender y desde el punto de vista del autor logra desenmarañarlo con sencillez.

En suma, se trata de un articulo en el que la agilidad de su lectura no conspira contra la profundidad de sus conceptos. Sin duda (y tal vez este sea su mérito mayor) causará en el lector inquieto el deseo de abrevar de las mismas fuentes de las que el autor se han nutrido en un tema que perceptiblemente parece simple y ser lo mismo, cuando en realidad se trata de aspectos fisiológicos intimamente relacionados, pero distintos en sus principios.